By 1988 I had already become quite familiar with Baja California, particularly the northern state where we had been monitoring Least Terns and Light-footed Clapper Rails in the coastal marshes. But probably an overview would be helpful here as the peninsula is still unfamiliar to a lot of people on this side of the border. The northernmost marsh is Estero de Punta Banda, just south of Ensenada, and the next on is 75 mi. south and just west of the town of San Quintin. These are in Baja California Norte. In B.C. Sur there are 3 huge estuaries, Guerro Negro where there is a giant saltworks on one of the inner lagoons, Laguna San Ignacio, famous as a winter nursery for the Gray Whale, and Bahia Magdalen – a the farthest south. The east coast of the peninsula has some grand bays but very little marshland – all the great saltmarshes are on the Pacific Coast. All of them have rails and terns and all are targets for development. When pro esteros was begun there were few NGOs in Mexico and only two committed to environmental concerns – Friends of the Biosphere Reserve was founded in Yucatan and focussed on the reserve, and Pro Natura, an important group on the mainland, but with no presence in Baja California. Volunteerism was not a common practice at the ti me and communication was far more difficult than in U.S. I learned fast how different it was going to be to be get the Mexican chapter started. I remember discussing with Silvia early on how to advertise our new venture, how to reach potential members, how to get the word out in Ensenada about the threat to the estuary. The mail was simply not useful or even used, telephoning was quite good but time consuming and inefficient for reaching out to more than friends, leaflets were commonly used but more for announcing concerts and such events and not likely to be effective for us. Within a few years email made a huge difference to our operations, but initially most communication was word of mouth! Nevertheless it worked and the membership grew, although slower than the U.S. chapter. Here is a photo of Silvia and me at an annual meeting.

me and communication was far more difficult than in U.S. I learned fast how different it was going to be to be get the Mexican chapter started. I remember discussing with Silvia early on how to advertise our new venture, how to reach potential members, how to get the word out in Ensenada about the threat to the estuary. The mail was simply not useful or even used, telephoning was quite good but time consuming and inefficient for reaching out to more than friends, leaflets were commonly used but more for announcing concerts and such events and not likely to be effective for us. Within a few years email made a huge difference to our operations, but initially most communication was word of mouth! Nevertheless it worked and the membership grew, although slower than the U.S. chapter. Here is a photo of Silvia and me at an annual meeting.

In late 1991 Silvia had to resign, as she was required by CICESE to pursue a 2nd PhD to keep her position. Two difficult and uncertain years foll owed and the future of the Mexican chapter was at hazard until Laura Martinez Rios became chair in 1993. Laura had been active since the beginning and was currently Secretary. Her sister Patricia Martinez joined her and soon the chapter was again humming with activity, and new directions. They were a marvelous team and continued to run the chapter together for 20 years until Patricia’s untimely death in 2013. Now Laura is carrying on alone.

owed and the future of the Mexican chapter was at hazard until Laura Martinez Rios became chair in 1993. Laura had been active since the beginning and was currently Secretary. Her sister Patricia Martinez joined her and soon the chapter was again humming with activity, and new directions. They were a marvelous team and continued to run the chapter together for 20 years until Patricia’s untimely death in 2013. Now Laura is carrying on alone.

Laura is at left in the photo, with Charlie Moore (board member) and me.

Laura and Patricia had an easy way with people and seemed to know just what would work. We learned so much from them; they were ‘community organizers’ before the tern was invented. They quickly formed alliances with teachers and others in Punta Banda, San Quintin and San Ignacio and began to get local people involved in conservation. These towns were small and isolated, even from Mexico itself, which paid little attention to its outlying peninsula. They were very good at finding projects that would catch people’s imagination. As an example, they started a very special school program that came into being in 1996 – the Brant project. The Brant is a Pacific coast goose that breeds in northern Alaska and spends the winter in the bays of Baja California, including San Quintin. A project was begun with secondary school students in San Quintin, Coos Bay Oregon, Padilla Bay Washington, a British Columbia school, and Cold Bay Alaska to track the birds’ migration. Personal computers and email were a very recent and welcome boon to correspondence in such outlying places. The students in Alaska would note when the birds left in the autumn and email students in the other schools along the migratory route who would watch for Brant arrivals and report them back. It was a chain of communication that was utterly innovative and caught on fast with the kids.

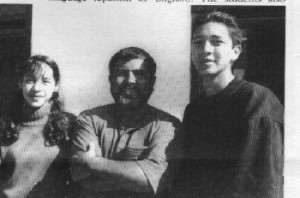

The biggest momen t came when they were invited to send representatives to the International Coastal Zone 1997 Conference in Boston. A Lannan Foundation grant provided funds for students from each school to attend. Afterward the meeting they toured coastal reserves on Cape Cod with a NOAA scientist. What an imaginative way to teach kids field biology and international collaboration in science! Here is a photo of Carlos Sepulveda (pro esteros biologist) at the conference, with the two students who attended.

t came when they were invited to send representatives to the International Coastal Zone 1997 Conference in Boston. A Lannan Foundation grant provided funds for students from each school to attend. Afterward the meeting they toured coastal reserves on Cape Cod with a NOAA scientist. What an imaginative way to teach kids field biology and international collaboration in science! Here is a photo of Carlos Sepulveda (pro esteros biologist) at the conference, with the two students who attended.

An article about the project in the pro esteros newsletter of Autumn 1996 reported:

“Hi, everyone from the pro esteros office in Ensenada ——- Having a computer hooked up to email has created a lot of excitement in San Quintin. Everyone comes to school to see for themselves how it works. The students tell them about out monitoring project and how important the wetlands are for Brant. Also I am pleased to report that the Secretary of Tourism for the State of Baja California (Norte), having heard about our Brant project, he just announced that he will include the annual arrival of the Brant in his brochure of important eco-tourist attractions. Laura Martinez Rios”

The crisis at Estero de Punta Banda was the first of many, and the creation of pro esteros was certainly opportune. Plans for major developments in and around Baja California’s estuaries kept surfacing in the 1990s, each one more devastating than the last, and in every one pro esteros was deeply involved. They were all defeated. It would take a lot of writing to describe all these events and I can only mention them here. They kept us busy. First the barrier beach at San Quintin, a glorious and near-pristine ecosystem, went up for sale. By then we had some very fine granting agencies supporting our work, including the Packard, Hewlett, Will J. Reid, Lannan and Homeland Foundations. We began to think about buying threatened acreage, but soon found that non-Mexicans could not buy coastal land. Next an expansive Japanese golf resort was proposed for on the barrier beach at San Quintin.

The biggest and worst of all proposals was for a huge extension of the Guerro Negro saltworks; this one garnered international opposition. It would have obliterated the natural landscape from Guerro Negro to San Ignacio Lagoon and turned the whole inner reach of the lagoon into another saltworks. Sometimes it seemed that most of our efforts were in erecting defenses against exploitation; but the satisfaction of helping to prevent the destruction of these wonderful natural resources was truly great. And with each one there was more publicity; for the saltworks plan the Natural Resources Defence Council was the main player and Robert Kennedy led their fight. In March 2000 Mexican President Zedillo cancelled the project, an exhilerating moment for conservationists everywhere. Here is a wonderful photo of Patricia taken at San Ignacio Lagoon with Jean Michel Cousteau, who was there with an NRDC fact-finding group in 1997.